Who First Pened the Words Neer a Grecian Art Did Trace a Finer Form More Lovely Face

Unknown Venetian artist, The Reception of the Ambassadors in Damascus, 1511, Louvre. The deer with antlers in the foreground is non known ever to have existed in the wild in Syria.

In art history, literature and cultural studies, Orientalism is the false or depiction of aspects in the Eastern world. These depictions are usually washed by writers, designers, and artists from the Western world. In particular, Orientalist painting, depicting more than specifically the Middle East,[1] was one of the many specialisms of 19th-century academic art, and the literature of Western countries took a similar interest in Oriental themes.

Since the publication of Edward Said'south Orientalism in 1978, much bookish discourse has begun to use the term "Orientalism" to refer to a general patronizing Western attitude towards Center Eastern, Asian, and North African societies. In Said's analysis, the Westward essentializes these societies as static and undeveloped—thereby fabricating a view of Oriental civilization that can be studied, depicted, and reproduced in the service of majestic power. Implicit in this fabrication, writes Said, is the idea that Western gild is adult, rational, flexible, and superior.[ii]

Background [edit]

Etymology [edit]

Orientalism refers to the Orient, in reference and opposition to the Occident; the E and the Westward, respectively.[3] [4] The word Orient entered the English linguistic communication every bit the Middle French orient. The root word oriēns, from the Latin Oriēns, has synonymous denotations: The eastern part of the globe; the sky whence comes the sun; the due east; the rising lord's day, etc.; yet the denotation changed every bit a term of geography.

In the "Monk's Tale" (1375), Geoffrey Chaucer wrote: "That they conquered many regnes grete / In the orient, with many a off-white citee." The term orient refers to countries eastward of the Mediterranean Sea and Southern Europe. In In Identify of Fear (1952), Aneurin Bevan used an expanded denotation of the Orient that comprehended East Asia: "the enkindling of the Orient nether the touch of Western ideas." Edward Said said that Orientalism "enables the political, economic, cultural and social domination of the West, not but during colonial times, simply as well in the present."[v]

Art [edit]

In fine art history, the term Orientalism refers to the works of generally 19th-century Western artists who specialized in Oriental subjects, produced from their travels in Western Asia, during the 19th century. In that time, artists and scholars were described as Orientalists, especially in French republic, where the dismissive employ of the term "Orientalist" was fabricated popular by the art critic Jules-Antoine Castagnary.[6] Despite such social disdain for a manner of representational art, the French Society of Orientalist Painters was founded in 1893, with Jean-Léon Gérôme equally the honorary president;[7] whereas in Great britain, the term Orientalist identified "an artist."[8]

The formation of the French Orientalist Painters Gild inverse the consciousness of practitioners towards the end of the 19th century, since artists could now meet themselves every bit part of a distinct fine art motion.[9] As an art motility, Orientalist painting is generally treated every bit one of the many branches of 19th-century academic fine art; nonetheless, many unlike styles of Orientalist art were in prove. Art historians tend to identify two broad types of Orientalist artist: the realists who carefully painted what they observed and those who imagined Orientalist scenes without ever leaving the studio.[10] French painters such as Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) and Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904) are widely regarded as the leading luminaries of the Orientalist motion.[xi]

Oriental studies [edit]

Professor G. A. Wallin (1811–1852), a Finnish explorer and orientalist, who was remembered for beingness one of the starting time Europeans to study and travel in the Middle Due east during the 1840s.[12] [13] [14] Portrait of Wallin by R. W. Ekman, 1853.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the term Orientalist identified a scholar who specialized in the languages and literatures of the Eastern earth. Amid such scholars were officials of the East India Visitor, who said that the Arab civilisation, the Indian culture, and the Islamic cultures should be studied as equal to the cultures of Europe.[15] Amidst such scholars is the philologist William Jones, whose studies of Indo-European languages established modern philology. Company rule in India favored Orientalism equally a technique for developing and maintaining positive relations with the Indians—until the 1820s, when the influence of "anglicists" such every bit Thomas Babington Macaulay and John Stuart Mill led to the promotion of a Western-style education.[sixteen]

Additionally, Hebraism and Jewish studies gained popularity among British and German scholars in the 19th and 20th centuries.[17] The bookish field of Oriental studies, which comprehended the cultures of the Near East and the Far East, became the fields of Asian studies and Middle Eastern studies.

Critical studies [edit]

Edward Said [edit]

In his book Orientalism (1978), cultural critic Edward Said redefines the term Orientalism to describe a pervasive Western tradition—academic and artistic—of prejudiced outsider-interpretations of the Eastern world, which was shaped past the cultural attitudes of European imperialism in the 18th and 19th centuries.[18] The thesis of Orientalism develops Antonio Gramsci'south theory of cultural hegemony, and Michel Foucault's theorisation of discourse (the knowledge-ability relation) to criticise the scholarly tradition of Oriental studies. Said criticised contemporary scholars who perpetuated the tradition of outsider-interpretation of Arabo-Islamic cultures, especially Bernard Lewis and Fouad Ajami.[19] [20] Furthermore, Said said that "The idea of representation is a theatrical one: the Orient is the phase on which the whole Eastward is confined",[21] and that the subject of learned Orientalists "is non so much the East itself equally the Due east fabricated known, and therefore less fearsome, to the Western reading public".[22]

In the academy, the book Orientalism (1978) became a foundational text of post-colonial cultural studies.[xx] The analyses in Said's works are of Orientalism in European literature, especially French literature, and do not analyse visual art and Orientalist painting. In that vein, the art historian Linda Nochlin applied Said's methods of critical analysis to art, "with uneven results".[23] Other scholars come across Orientalist paintings as depicting a myth and a fantasy that didn't often correlate with reality.[24]

There is also a critical trend within the Islamic earth. In 2002 it was estimated that in Saudi arabia alone some 200 books and 2000 manufactures discussing Orientalism had been penned by local or foreign scholars.[25]

Soviet scholarship [edit]

From the Bolsháya sovétskaya entsiklopédiya (1951):[26]

Reflecting the colonialist-racist worldview of the European and American bourgeoisie, from the very beginning bourgeois orientology diametrically opposed the civilizations of the then-called "West" with those of the "East" slanderously declaring that Asian peoples are racially inferior, somehow primordially backward, incapable of determining their own fates, and that they appeared merely every bit history's objects rather than its subject area.

In European architecture and design [edit]

The Moresque fashion of Renaissance ornamentation is a European adaptation of the Islamic arabesque that began in the late 15th century and was to be used in some types of work, such every bit bookbinding, until well-nigh the present day. Early on architectural employ of motifs lifted from the Indian subcontinent is known every bit Indo-Saracenic Revival architecture. One of the primeval examples is the façade of Guildhall, London (1788–1789). The style gained momentum in the west with the publication of views of India by William Hodges, and William and Thomas Daniell from about 1795. Examples of "Hindoo" architecture are Sezincote Firm (c. 1805) in Gloucestershire, built for a nabob returned from Bengal, and the Majestic Pavilion in Brighton.

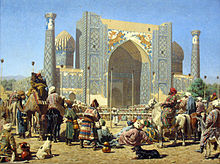

Turquerie, which began as early as the belatedly 15th century, continued until at least the 18th century, and included both the use of "Turkish" styles in the decorative arts, the adoption of Turkish costume at times, and involvement in art depicting the Ottoman Empire itself. Venice, the traditional trading partner of the Ottomans, was the earliest centre, with France becoming more prominent in the 18th century.

Chinoiserie is the catch-all term for the manner for Chinese themes in ornament in Western Europe, offset in the late 17th century and peaking in waves, especially Rococo Chinoiserie, c. 1740–1770. From the Renaissance to the 18th century, Western designers attempted to imitate the technical sophistication of Chinese ceramics with only partial success. Early hints of Chinoiserie appeared in the 17th century in nations with active Due east India companies: England (the Eastward India Company), Denmark (the Danish East Bharat Company), the Netherlands (the Dutch East India Company) and France (the French East Bharat Company). Tin-glazed pottery made at Delft and other Dutch towns adopted genuine Ming-era blueish and white porcelain from the early 17th century. Early on ceramic wares fabricated at Meissen and other centers of true porcelain imitated Chinese shapes for dishes, vases and teawares (see Chinese export porcelain).

Pleasure pavilions in "Chinese gustatory modality" appeared in the formal parterres of late Baroque and Rococo German language palaces, and in tile panels at Aranjuez well-nigh Madrid. Thomas Chippendale's mahogany tea tables and red china cabinets, especially, were embellished with fretwork glazing and railings, c. 1753–70. Sober homages to early Xing scholars' furnishings were as well naturalized, equally the tang evolved into a mid-Georgian side table and squared slat-dorsum armchairs that suited English gentlemen as well as Chinese scholars. Non every adaptation of Chinese design principles falls within mainstream "chinoiserie". Chinoiserie media included imitations of lacquer and painted tin (tôle) ware that imitated japanning, early on painted wallpapers in sheets, and ceramic figurines and table ornaments. Pocket-sized pagodas appeared on chimneypieces and full-sized ones in gardens. Kew has a magnificent Nifty Pagoda designed by William Chambers. The Wilhelma (1846) in Stuttgart is an example of Moorish Revival compages. Leighton Firm, built for the artist Frederic Leighton, has a conventional facade simply elaborate Arab-way interiors, including original Islamic tiles and other elements as well as Victorian Orientalizing work.

Subsequently 1860, Japonism, sparked by the importing of ukiyo-east, became an important influence in the western arts. In particular, many modern French artists such every bit Claude Monet and Edgar Degas were influenced by the Japanese style. Mary Cassatt, an American artist who worked in French republic, used elements of combined patterns, flat planes and shifting perspective of Japanese prints in her own images.[27] The paintings of James Abbott McNeill Whistler's The Peacock Room demonstrated how he used aspects of Japanese tradition and are some of the finest works of the genre. California architects Greene and Greene were inspired past Japanese elements in their pattern of the Take a chance House and other buildings.

Egyptian Revival architecture became popular in the early and mid-19th century and continued as a minor style into the early 20th century. Moorish Revival architecture began in the early 19th century in the German states and was specially popular for building synagogues. Indo-Saracenic Revival architecture was a genre that arose in the tardily 19th century in the British Raj.

-

Chinesischer Turm (Chinese Tower) in the Englischer Garten, Munich, Frg: The initial structure was congenital 1789–1790.

Orientalist art [edit]

Pre-19th century [edit]

Depictions of Islamic "Moors" and " Turks" (imprecisely named Muslim groups of southern Europe, N Africa and Due west Asia) tin can be constitute in Medieval, Renaissance, and Baroque art. In Biblical scenes in Early Netherlandish painting, secondary figures, especially Romans, were given exotic costumes that distantly reflected the clothes of the Near E. The Three Magi in Nativity scenes were an especial focus for this. In general art with Biblical settings would not be considered every bit Orientalist except where contemporary or historicist Middle Eastern detail or settings is a characteristic of works, as with some paintings by Gentile Bellini and others, and a number of 19th-century works. Renaissance Venice had a phase of particular interest in depictions of the Ottoman Empire in painting and prints. Gentile Bellini, who travelled to Constantinople and painted the Sultan, and Vittore Carpaccio were the leading painters. By so the depictions were more accurate, with men typically dressed all in white. The depiction of Oriental carpets in Renaissance painting sometimes draws from Orientalist interest, but more than often simply reflects the prestige these expensive objects had in the period.[28]

Jean-Étienne Liotard (1702–1789) visited Istanbul and painted numerous pastels of Turkish domestic scenes; he besides continued to wearable Turkish attire for much of the time when he was back in Europe. The ambitious Scottish 18th-century artist Gavin Hamilton found a solution to the problem of using modern dress, considered unheroic and inelegant, in history painting past using Middle Eastern settings with Europeans wearing local costume, every bit travelers were advised to exercise. His huge James Dawkins and Robert Wood Discovering the Ruins of Palmyra (1758, at present Edinburgh) elevates tourism to the heroic, with the two travelers wearing what wait very like togas. Many travelers had themselves painted in exotic Eastern dress on their return, including Lord Byron, as did many who had never left Europe, including Madame de Pompadour.[29] The growing French involvement in exotic Oriental luxury and lack of liberty in the 18th century to some extent reflected a pointed analogy with France's ain accented monarchy.[30] Byron'south poetry was highly influential in introducing Europe to the heady cocktail of Romanticism in exotic Oriental settings which was to dominate 19th century Oriental fine art.

French Orientalism [edit]

French Orientalist painting was transformed past Napoleon'southward ultimately unsuccessful invasion of Egypt and Syria in 1798–1801, which stimulated bully public involvement in Egyptology, and was also recorded in subsequent years by Napoleon'due south court painters, particularly Antoine-Jean Gros, although the Middle Eastern campaign was non 1 on which he accompanied the army. Two of his most successful paintings, Bonaparte Visiting the Plague Victims of Jaffa (1804) and Battle of Abukir (1806) focus on the Emperor, equally he was by and so, just include many Egyptian figures, as does the less effective Napoleon at the Battle of the Pyramids (1810). Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson'due south La Révolte du Caire (1810) was another large and prominent case. A well-illustrated Clarification de l'Égypte was published by the French Government in twenty volumes between 1809 and 1828, concentrating on antiquities.[31]

Eugène Delacroix's first great success, The Massacre at Chios (1824) was painted before he visited Greece or the East, and followed his friend Théodore Géricault'southward The Raft of the Medusa in showing a recent incident in distant parts that had aroused public opinion. Greece was still fighting for independence from the Ottomans, and was effectively as exotic every bit the more than Near Eastern parts of the empire. Delacroix followed upwardly with Hellenic republic on the Ruins of Missolonghi (1827), commemorating a siege of the previous year, and The Death of Sardanapalus, inspired by Lord Byron, which although prepare in artifact has been credited with beginning the mixture of sex, violence, lassitude and exoticism which runs through much French Orientalist painting.[32] In 1832, Delacroix finally visited what is now People's democratic republic of algeria, recently conquered by the French, and Morocco, as part of a embassy to the Sultan of Morocco. He was greatly struck by what he saw, comparing the North African mode of life to that of the Ancient Romans, and continued to pigment subjects from his trip on his return to France. Like many later on Orientalist painters, he was frustrated by the difficulty of sketching women, and many of his scenes featured Jews or warriors on horses. Yet, he was manifestly able to get into the women's quarters or harem of a firm to sketch what became Women of Algiers; few later harem scenes had this merits to authenticity.[33]

When Ingres, the director of the French Académie de peinture, painted a highly colored vision of a Turkish bath, he made his eroticized Orient publicly acceptable by his diffuse generalizing of the female person forms (who might all take been the aforementioned model). More open up sensuality was seen every bit adequate in the exotic Orient.[34] This imagery persisted in art into the early on 20th century, equally evidenced in Henri Matisse's orientalist semi-nudes from his Nice menses, and his use of Oriental costumes and patterns. Ingres' pupil Théodore Chassériau (1819–1856) had already achieved success with his nude The Toilette of Esther (1841, Louvre) and equestrian portrait of Ali-Ben-Hamet, Caliph of Constantine and Main of the Haractas, Followed by his Escort (1846) before he first visited the Eastward, but in afterward decades the steamship fabricated travel much easier and increasing numbers of artists traveled to the Middle Eastward and beyond, painting a broad range of Oriental scenes.

In many of these works, they portrayed the Orient as exotic, colorful and sensual, not to say stereotyped. Such works typically full-bodied on Arab, Jewish, and other Semitic cultures, every bit those were the ones visited by artists as France became more engaged in Due north Africa. French artists such every bit Eugène Delacroix, Jean-Léon Gérôme and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres painted many works depicting Islamic culture, often including lounging odalisques. They stressed both lassitude and visual spectacle. Other scenes, specially in genre painting, have been seen as either closely comparable to their equivalents set in mod-twenty-four hours or historical Europe, or as as well reflecting an Orientalist heed-set in the Saidian sense of the term. Gérôme was the forerunner, and ofttimes the primary, of a number of French painters in the later on part of the century whose works were often frankly salacious, oft featuring scenes in harems, public baths and slave auctions (the last ii also bachelor with classical decor), and responsible, with others, for "the equation of Orientalism with the nude in pornographic manner";[35] (Gallery, beneath)

British Orientalism [edit]

Though British political interest in the territories of the unravelling Ottoman Empire was equally intense as in France, it was by and large more discreetly exercised. The origins of British Orientalist 19th-century painting owe more to religion than military conquest or the search for plausible locations for nude women. The leading British genre painter, Sir David Wilkie was 55 when he travelled to Istanbul and Jerusalem in 1840, dying off Gibraltar during the return voyage. Though not noted as a religious painter, Wilkie fabricated the trip with a Protestant agenda to reform religious painting, as he believed that: "a Martin Luther in painting is every bit much chosen for as in theology, to sweep abroad the abuses by which our divine pursuit is encumbered", past which he meant traditional Christian iconography. He hoped to find more than authentic settings and decor for Biblical subjects at their original location, though his death prevented more than studies existence made. Other artists including the Pre-Raphaelite William Holman Hunt and David Roberts (in The Holy State, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt, and Nubia) had similar motivations,[36] giving an emphasis on realism in British Orientalist art from the start.[37] The French artist James Tissot besides used contemporary Center Eastern landscape and decor for Biblical subjects, with little regard for historical costumes or other fittings.

William Holman Hunt produced a number of major paintings of Biblical subjects drawing on his Middle Eastern travels, improvising variants of contemporary Arab costume and furnishings to avoid specifically Islamic styles, and as well some landscapes and genre subjects. The biblical subjects included The Scapegoat (1856), The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple (1860), and The Shadow of Decease (1871). The Miracle of the Holy Fire (1899) was intended equally a picturesque satire on the local Eastern Christians, of whom, like most European visitors, Hunt took a very dim view. His A Street Scene in Cairo; The Lantern-Maker's Courting (1854–61) is a rare contemporary narrative scene, equally the beau feels his fiancé'due south confront, which he is not immune to run across, through her veil, as a Westerner in the background beats his way up the street with his stick.[38] This a rare intrusion of a clearly contemporary figure into an Orientalist scene; mostly they claim the picturesqueness of the historical painting and so popular at the fourth dimension, without the trouble of researching authentic costumes and settings.

When Gérôme exhibited For Sale; Slaves at Cairo at the Royal University in London in 1871, information technology was "widely institute offensive", partly because the British involvement in successfully suppressed the slave merchandise in Egypt, but also for cruelty and "representing fleshiness for its own sake".[39] Only Rana Kabbani believes that "French Orientalist painting, as exemplified past the works of Gérôme, may appear more sensual, gaudy, gory and sexually explicit than its British counterpart, but this is a deviation of style not substance ... Like strains of fascination and repulsion convulsed their artists"[40] Nonetheless, nudity and violence are more evident in British paintings set in the ancient globe, and "the iconography of the odalisque ... the Oriental sex slave whose image is offered up to the viewer as freely as she herself supposedly was to her principal – is almost entirely French in origin",[34] though taken upwards with enthusiasm by Italian and other European painters.

John Frederick Lewis, who lived for several years in a traditional mansion in Cairo, painted highly detailed works showing both realistic genre scenes of Middle Eastern life and more idealized scenes in upper grade Egyptian interiors with no traces of Western cultural influence yet apparent. His conscientious and seemingly affectionate representation of Islamic compages, effects, screens, and costumes set new standards of realism, which influenced other artists, including Gérôme in his afterwards works. He "never painted a nude", and his wife modelled for several of his harem scenes,[41] which, with the rare examples past the classicist painter Lord Leighton, imagine "the harem equally a place of near English domesticity, ... [where]... women's fully clothed respectability suggests a moral healthiness to go with their natural expert looks".[34]

Other artists concentrated on landscape painting, often of desert scenes, including Richard Dadd and Edward Lear. David Roberts (1796–1864) produced architectural and landscape views, many of antiquities, and published very successful books of lithographs from them.[42]

Russian Orientalism [edit]

Russian Orientalist art was largely concerned with the areas of Cardinal Asia that Russia was conquering during the century, and also in historical painting with the Mongols who had dominated Russia for much of the Centre Ages, who were rarely shown in a skilful light.[43] The explorer Nikolai Przhevalsky played a major role in popularising an exotic view of "the Orient" and advocating imperial expansion.[44]

"The Five" Russian composers were prominent 19th-century Russian composers who worked together to create a distinct national way of classical music. I authentication of "The Five" composers was their reliance on orientalism.[45] Many quintessentially "Russian" works were composed in orientalist style, such equally Balakirev'south Islamey, Borodin's Prince Igor and Rimsky-Korsakov's Scheherazade.[45] As leader of "The Five," Balakirev encouraged the use of eastern themes and harmonies to fix their "Russian" music autonomously from the High german symphonism of Anton Rubinstein and other Western-oriented composers.[45]

German language Orientalism [edit]

Edward Said originally wrote that Deutschland did not take a politically motivated Orientalism because its colonial empire did non expand in the same areas every bit France and U.k.. Said later on stated that Germany "had in common with Anglo-French and later American Orientalism [...] a kind of intellectual authority over the Orient," Yet, Said as well wrote that "there was nix in Federal republic of germany to correspond to the Anglo-French presence in Republic of india, the Levant, North Africa. Moreover, the German Orient was almost exclusively a scholarly, or at least a classical, Orient: it was made the bailiwick of lyrics, fantasies, and even novels, but it was never bodily."[46] According to Suzanne L. Marchand, German scholars were the "stride-setters" in oriental studies.[47] Robert Irwin wrote that "until the outbreak of the Second Globe State of war, German dominance of Orientalism was practically unchallenged."[48]

Elsewhere [edit]

Nationalist historical painting in Central Europe and the Balkans dwelt on oppression during the Ottoman Empire period, battles between Ottoman and Christian armies, as well as themes like the Ottoman Imperial Harem, although the latter was a less mutual theme than in French depictions.[49]

The Saidian assay has not prevented a strong revival of interest in, and collecting of, 19th century Orientalist works since the 1970s, the latter was in large part led past Middle Eastern buyers.[50]

Pop civilization [edit]

Authors and composers are not commonly referred to equally "Orientalist" in the way that artists are, and relatively few specialized in Oriental topics or styles, or are even best known for their works including them. Just many major figures, from Mozart to Flaubert, have produced significant works with Oriental subjects or treatments. Lord Byron with his four long "Turkish tales" in verse, is 1 of the most important writers to brand exotic fantasy Oriental settings a meaning theme in the literature of Romanticism. Giuseppe Verdi's opera Aida (1871) is set in Arab republic of egypt as portrayed through the content and the visual spectacle. "Aida" depicts a militaristic Egypt's tyranny over Ethiopia.[51]

Irish Orientalism had a particular character, cartoon on various beliefs well-nigh early on historical links between Ireland and the East, few of which are now regarded every bit historically correct. The mythical Milesians are one example of this. The Irish were also witting of the views of other nations seeing them as comparably backward to the E, and Europe'due south "backyard Orient."[52]

In music [edit]

In music, Orientalism may exist applied to styles occurring in different periods, such equally the alla Turca, used by multiple composers including Mozart and Beethoven.[53] The American musicologist Richard Taruskin has identified in 19th-century Russian music a strain of Orientalism: "the Due east as a sign or metaphor, as imaginary geography, as historical fiction, as the reduced and totalized other against which we construct our (not less reduced and totalized) sense of ourselves."[54] Taruskin concedes Russian composers, unlike those in France and Frg, felt an "ambivalence" to the theme since "Russia was a contiguous empire in which Europeans, living side past side with 'orientals', identified (and intermarried) with them far more than in the instance of other colonial powers".[55]

Nonetheless, Taruskin characterizes Orientalism in Romantic Russian music as having melodies "total of close petty ornaments and melismas,"[56] chromatic accompanying lines, drone bass[57]—characteristics which were used by Glinka, Balakirev, Borodin, Rimsky-Korsakov, Lyapunov, and Rachmaninov. These musical characteristics evoke:[57]

non just the East, but the seductive East that emasculates, enslaves, renders passive. In a discussion, it signifies the hope of the experience of nega, a prime attribute of the orient equally imagined past the Russians.... In opera and song, nega oftentimes just denotes Due south-Eastward-X a la russe, desired or achieved.

Orientalism is as well traceable in music that is considered to have effects of exoticism, including the Japonisme in Claude Debussy's pianoforte music all the way to the sitar beingness used in recordings by the Beatles.[53]

In the United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland, Gustav Holst equanimous Beni Mora evoking a languid, heady Arabian temper.

Orientalism, in a more military camp mode besides constitute its fashion into exotica music in the late 1950s, especially the works of Les Baxter, for example, his composition "City of Veils."

In literature [edit]

The Romantic movement in literature began in 1785 and ended around 1830. The term Romantic references the ideas and culture that writers of the fourth dimension reflected in their work. During this time, the civilization and objects of the East began to have a profound effect on Europe. Extensive traveling past artists and members of the European elite brought travelogues and sensational tales back to the West creating a great interest in all things "foreign." Romantic Orientalism incorporates African and Asian geographic locations, well-known colonial and "native" personalities, sociology, and philosophies to create a literary surround of colonial exploration from a distinctly European worldview. The current trend in analysis of this movement references a belief in this literature equally a mode to justify European colonial endeavors with the expansion of territory.[58]

In his novel Salammbô, Gustave Flaubert used ancient Carthage in North Africa as a foil to ancient Rome. He portrayed its civilisation as morally corrupting and suffused with dangerously alluring eroticism. This novel proved hugely influential on later portrayals of ancient Semitic cultures.

In pic [edit]

Said argues that the continuity of Orientalism into the nowadays tin be found in influential images, specially through the Movie house of the Usa, every bit the West has at present grown to include the United States.[59] Many blockbuster feature motion-picture show, such every bit the Indiana Jones serial, The Mummy films, and Disney'due south Aladdin film serial demonstrate the imagined geographies of the Eastward.[59] The films usually portray the lead heroic characters equally being from the Western earth, while the villains often come up from the Eastward.[59] The representation of the Orient has continued in film, although this representation does not necessarily take whatsoever truth to it.

The overly sexualized graphic symbol of Princess Jasmine in Aladdin is simply a continuation of the paintings from the 19th century, where women were represented as erotic, sexualized fantasies.[60] [ neutrality is disputed]

In The Tea House of the Baronial Moon (1956), equally argued by Pedro Iacobelli, there are tropes of orientalism. He notes, that the film "tells us more than most the Americans and the American's image of Okinawa rather than most the Okinawan people."[61] The moving-picture show characterizes the Okinawans equally "merry but backward" and "de-politicized," which ignored the real-life Okinawan political protests over forceful land acquisition past the American military at the time.

Kimiko Akita, in Orientalism and the Binary of Fact and Fiction in 'Memoirs of a Geisha', argues that Memoirs of a Geisha (2005) contains orientalist tropes and deep "cultural misrepresentations." She states that Memoirs of a Geisha "reinforces the idea of Japanese culture and geisha as exotic, astern, irrational, muddied, profane, promiscuous, bizarre, and enigmatic."

In dance [edit]

During the Romantic period of the 19th century, ballet developed a preoccupation with the exotic. This exoticism ranged from ballets set in Scotland to those based on ethereal creatures.[62] [ commendation needed ] Past the afterwards office of the century, ballets were capturing the presumed essence of the mysterious East. These ballets often included sexual themes and tended to be based on assumptions of people rather than on concrete facts. Orientalism is credible in numerous ballets.

The Orient motivated several major ballets, which have survived since the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Le Corsaire premiered in 1856 at the Paris Opera, with choreography by Joseph Mazilier.[63] Marius Petipa re-choreographed the ballet for the Maryinsky Ballet in Saint petersburg, Russia in 1899.[63] Its complex storyline, loosely based on Lord Byron'southward poem,[64] takes place in Turkey and focuses on a love story between a pirate and a cute slave daughter. Scenes include a bazaar where women are sold to men every bit slaves, and the Pasha'southward Palace, which features his harem of wives.[63] In 1877, Marius Petipa choreographed La Bayadère, the love story of an Indian temple dancer and Indian warrior. This ballet was based on Kalidasa's play Sakuntala.[64] La Bayadere used vaguely Indian costuming, and incorporated Indian inspired hand gestures into classical ballet. In addition, information technology included a 'Hindu Trip the light fantastic toe,' motivated by Kathak, an Indian trip the light fantastic toe form.[64] Another ballet, Sheherazade, choreographed by Michel Fokine in 1910 to music past Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, is a story involving a shah's married woman and her illicit relations with a Gilt Slave, originally played by Vaslav Nijinsky.[64] The ballet's controversial fixation on sexual activity includes an orgy in an oriental harem. When the shah discovers the deportment of his numerous wives and their lovers, he orders the deaths of those involved.[64] Sheherazade was loosely based on folktales of questionable authenticity.

Several lesser-known ballets of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century besides evidence their Orientalism. For example, in Petipa's The Pharaoh's Daughter (1862), an Englishman imagines himself, in an opium-induced dream, every bit an Egyptian boy who wins the love of the Pharaoh'due south girl, Aspicia.[64] Aspicia'south costume consisted of 'Egyptian' décor on a tutu.[64] Another ballet, Hippolyte Monplaisir'due south Brahma, which premiered in 1868 in La Scala, Italy,[65] is a story that involves romantic relations between a slave girl and Brahma, the Hindu god, when he visits earth.[64] In addition, in 1909, Serge Diagilev included Cléopâtre in the Ballets Russes' repertory. With its theme of sex, this revision of Fokine'southward Une Nuit d'Egypte combined the "exoticism and grandeur" that audiences of this fourth dimension craved.[64]

As one of the pioneers of mod trip the light fantastic toe in America, Ruth St Denis as well explored Orientalism in her dancing. Her dances were not authentic; she drew inspiration from photographs, books, and later from museums in Europe.[64] Still, the exoticism of her dances catered to the interests of gild women in America.[64] She included Radha and The Cobras in her 'Indian' program in 1906. In improver, she constitute success in Europe with another Indian-themed ballet, The Nautch in 1908. In 1909, upon her return to America, St Denis created her get-go 'Egyptian' work, Egypta.[64] Her preference for Orientalism continued, culminating with Ishtar of the Seven Gates in 1923, about a Babylonian goddess.[64]

While Orientalism in trip the light fantastic toe climaxed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it is still present in modern times. For instance, major ballet companies regularly perform Le Corsaire, La Bayadere, and Sheherazade. Furthermore, Orientalism is also found within newer versions of ballets. In versions of The Nutcracker, such equally the 2010 American Ballet Theatre production, the Chinese trip the light fantastic toe uses an arm position with the arms bent at a ninety-degree bending and the alphabetize fingers pointed upwards, while the Arabian trip the light fantastic uses two dimensional aptitude arm movements. Inspired by ballets of the past, stereotypical 'Oriental' movements and arm positions have developed and remain.

Organized religion [edit]

An exchange of Western and Eastern ideas about spirituality adult as the West traded with and established colonies in Asia.[66] The first Western translation of a Sanskrit text appeared in 1785,[67] marking the growing interest in Indian culture and languages.[68] Translations of the Upanishads, which Arthur Schopenhauer called "the alleviation of my life", first appeared in 1801 and 1802.[69] [note i] Early translations as well appeared in other European languages.[71] 19th-century transcendentalism was influenced by Asian spirituality, prompting Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882) to pioneer the idea of spirituality as a distinct field.[72]

A major force in the mutual influence of Eastern and Western spirituality and religiosity was the Theosophical Society,[73] [74] a grouping searching for ancient wisdom from the E and spreading Eastern religious ideas in the West.[75] [66] One of its salient features was the conventionalities in "Masters of Wisdom",[76] [note 2] "beings, human or once human, who have transcended the normal frontiers of noesis, and who brand their wisdom available to others".[76] The Theosophical Guild as well spread Western ideas in the East, contributing to its modernisation and a growing nationalism in the Asian colonies.[66]

The Theosophical Society had a major influence on Buddhist modernism[66] and Hindu reform movements.[74] [66] Between 1878 and 1882, the Society and the Arya Samaj were united as the Theosophical Club of the Arya Samaj.[77] Helena Blavatsky, along with H. South. Olcott and Anagarika Dharmapala, was instrumental in the Western manual and revival of Theravada Buddhism.[78] [79] [80]

Some other major influence was Vivekananda,[81] [82] who popularised his modernised interpretation[83] of Advaita Vedanta during the later 19th and early on 20th century in both India and the Westward,[82] emphasising anubhava ("personal feel") over scriptural authorization.[84]

Islam [edit]

With the spread of Eastern religious and cultural ethics towards the Due west, came in with studies and certain illustrations that depicts sure regions and religions under the Western perspective. Many the aspects or views are oftentimes turned into the ideas that the West accept adopted onto those cultural and religious ideals. I of the more adopted views can be depicted through Western context on Islam and the Eye East. Under the adopted view of Islam under the Western context, Orientalism falls nether the category of the Western perspective of thinking that shifts through social constructs that refers towards representations of the religion or culture in a subjective view bespeak.[85] The concept of Orientalism dates dorsum to precolonial eras, as the main European powers acquired and perceived of territory, resources, knowledge, and control of the regions in the East.[85] The term Orientalism, depicts further into the historical context of animosity and misrepresentation into the tendencies of a growing layer of Western inclusion and influence on foreign culture and ethics.[86]

In the religious perspective under Islam, the term Orientalism applies in similar meaning as the outlook from the Western perspective, mainly in the eyes of the Christian bulk.[86] The primary contributor of the delineation of Oriental perspectives or illustrations on Islam and other Middle Eastern cultures derives from the imperial and colonial influences and powers that attribute to germination of multiple fields of geographical, political, educational, and scientific elements.[86] The combination of these different genres reveal significant division among people of those cultures and reinforces the ideals set from the Western perspective.[86] With Islam, historically scientific discoveries, inquiry, inventions, or ideas that were presented before and contributed to many other European breakthroughs are not affiliated with the previous Islamic scientists.[86] From the exclusion of past contributions and initial works further pb to narrative of the concept of Orientalism with the passing of time generated a history and directive of presence within region and religion that historically influences the image of the East.[85]

Through the recent years, Orientalism has been influenced and shirted to altering representations of various forms that all derive from the same meaning.[85] From the nineteenth century, among the Western perspectives on Orientalism, differed equally the split up of American and European Orientalism viewed different illustrations.[85] With mainstream media and pop product reveal many depictions of Oriental cultures and Islamic references to the current result of radicalization for Non-western cultures.[85] With references and mainstream media often utilized to contribute to an extended agenda nether the construct judgement of alternating motives.[85] The arroyo with the generalization of the term Orientalism was embedded with nether start of colonialism as the root of the main complexity of inside modernistic societies perspectives of foreign cultures.[86] Equally mainstream media depicts illustrations to utilize many instances of discourse and on certain regions mainly amidst the conflict inside regions in the Center East and Africa.[86] With calendar of influencing views on non-western societies to be accounted not-compatible with differing ideologies and cultures, the elements that present diversion among Eastern societies and aspects.[86]

Eastern views of the West and Western views of the Due east [edit]

The concept of Orientalism has been adopted past scholars in East-Fundamental and Eastern Europe, amongst them Maria Todorova, Attila Melegh, Tomasz Zarycki, and Dariusz Skórczewski[87] as an analytical tool for exploring the images of East-Cardinal and Eastern European societies in cultural discourses of the West in the 19th century and during the Soviet domination.

The term "re-orientalism" was used past Lisa Lau and Ana Cristina Mendes[88] [89] to refer to how Eastern self-representation is based on western referential points:[xc]

Re-Orientalism differs from Orientalism in its manner of and reasons for referencing the West: while challenging the metanarratives of Orientalism, re-Orientalism sets up culling metanarratives of its own in society to articulate eastern identities, simultaneously deconstructing and reinforcing Orientalism.

Occidentalism [edit]

The term occidentalism is often used to refer to negative views of the Western world establish in Eastern societies, and is founded on the sense of nationalism that spread in reaction to colonialism[91] (come across Pan-Asianism). Edward Said has been defendant of Occidentalizing the w in his critique of Orientalism; of being guilty of falsely characterizing the Westward in the same mode that he accuses Western scholars of falsely characterizing the Due east.[92] Said essentialized the West past creating a homogenous image of the area. Currently, the Westward consists not only of Europe, only also the United States and Canada, which accept become more than influential over the years.[92]

Othering [edit]

The action of othering cultures occurs when groups are labeled every bit different due to characteristics that distinguish them from the perceived norm.[93] Edward Said, author of the book Orientalism, argued that western powers and influential individuals such as social scientists and artists othered "the Orient."[86] The evolution of ideologies is frequently initially embedded in the linguistic communication, and continues to ripple through the material of society by taking over the culture, economy and political sphere.[94] Much of Said's criticism of Western Orientalism is based on what he describes as articularizing trends. These ideologies are present in Asian works by Indian, Chinese, and Japanese writers and artists, in their views of Western culture and tradition. A peculiarly pregnant development is the manner in which Orientalism has taken shape in non-Western cinema, every bit for instance in Hindi-language cinema.

Encounter likewise [edit]

- Allosemitism

- Arabist

- Black orientalism

- Borealism

- Chinoiserie

- Cultural appropriation

- Dahesh Museum

- Ethnocentrism

- Exoticism

- Hebraist

- Hellenocentrism

- Indomania

- Japonisme

- La belle juive

- List of artistic works with Orientalist influences

- List of Orientalist artists

- Neo-orientalism

- Noble savage

- Objectification

- Othering

- Outsider art

- Pizza effect

- Primitivism

- Racial fetishism

- Romantic racism

- Soviet Orientalist studies in Islam

- Stereotypes of Arabs and Muslims in the United States

- Stereotypes of Jews

- Stereotypes of South Asians

- Turquerie

- World music

- Xenocentrism

Notes [edit]

- ^ Schopenhauer also called his poodle "Atman".[70]

- ^ Encounter as well Ascended Master Teachings

References [edit]

- ^ Tromans, six

- ^ Mahmood Mamdani, Good Muslim, Bad Muslim: America, the Cold War, and the Roots of Terrorism, New York: Pantheon, 2004; ISBN 0-375-42285-4; p. 32.

- ^ Latin Oriens, Oxford English Dictionary. p. 000.

- ^ Said, Edward. "Orientalism," New York: Vintage Books, 1979. p. 364.

- ^ Said, Edward. "Orientalism," New York: Vintage Books, 1979: 357

- ^ Tromans, 20

- ^ Harding, 74

- ^ Tromans, 19

- ^ Benjamin, R., Orientalist Aesthetics: Fine art, Colonialism, and French Northward Africa, 1880-1930, 2003, pp 57 -78

- ^ Volait, Mercedes (2014). "Middle Eastern Collections of Orientalist Painting at the Turn of the 21st Century: Paradoxical Reversal or Persistent Misunderstanding?" (PDF). In Pouillon, François; Vatin, Jean-Claude (eds.). After Orientalism: Disquisitional perspectives on Western Agency and Eastern Reappropriations. Leiden Studies in Islam and Guild. Vol. two. pp. 251–271. doi:10.1163/9789004282537_019. ISBN9789004282520.

- ^ Encyclopedia.com, https://www.encyclopedia.com/literature-and-arts/art-and-architecture/fine art-general/orientalism

- ^ Notes Taken During a Journey Though Part of Northern Arabia in 1848. Published by the Imperial Geographical Society in 1851. (Online version.)

- ^ Narrative of a Journeys From Cairo to Medina and Mecca by Suez, Arabia, Tawila, Al-Jauf, Jubbe, Hail and Nejd, in 1845, Royal Geographical Society, 1854.

- ^ William R. Mead, G. A. Wallin and the Royal Geographical Society, Studia Orientalia 23, 1958.

- ^ Macfie, A. L. (2002). Orientalism. London: Longman. p. Ch One. ISBN978-0582423862.

- ^ Holloway (2006), pp. 1–2. "The Orientalism espoused by Warren Hastings, William Jones and the early Eastward India Company sought to maintain British domination over the Indian subcontinent through patronage of Hindu and Muslim languages and institutions, rather than through their eclipse by English language voice communication and aggressive European acculturation."

- ^ "Hebraists, Christian". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org . Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- ^ Tromans, 24

- ^ Orientalism (1978) Preface, 2003 ed. p. xv.

- ^ a b Xypolia, Ilia (2011). "Orientations and Orientalism: The Governor Sir Ronald Storrs". Periodical of IslamicJerusalem Studies. 11: 25–43.

- ^ Said, Edward W. (1979). Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books. p. 63. ISBN0-394-74067-X.

- ^ Said, Edward West. (1979). Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books. p. 60. ISBN0-394-74067-Ten.

- ^ Tromans, 6, 11 (quoted), 23–25

- ^ Marta Mamet–Michalkiewicz (2011). "Paradise Regained?: The Harem in Fatima Mernissi'due south Dreams of Trespass: Tales of a Harem Girlhood". In Helga Ramsey-Kurz and Geetha Ganapathy-Doré (ed.). Projections of Paradise. pp. 145–146. doi:10.1163/9789401200332_009. ISBN9789401200332.

- ^ Al-Samarrai, Qasim (2002). "Discussions on Orientalism in Present-Day Kingdom of saudi arabia". In Wiegers, Gerard (ed.). Modern Societies & the Science of Religions: Studies in Honor of Lammert Leertouwer. Numen Book Series. Vol. 95. pp. 283–301. doi:ten.1163/9789004379183_018. ISBN9789004379183. Page 284.

- ^ van der Oye, David (2010). Russian Orientalism. Yale Academy Press.

- ^ The subject of Ives

- ^ King and Sylvester, throughout

- ^ Christine Riding, Travellers and Sitters: The Orientalist Portrait, in Tromans, 48–75

- ^ Ina Baghdiantz McCabe (15 July 2008). Orientalism in Early on Modern France: Eurasian Trade, Exoticism and the Ancien Regime. Berg. p. 134. ISBN978-one-84520-374-0 . Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ^ Harding, 69–70

- ^ Nochlin, 294–296; Tromans, 128

- ^ Harding, 81

- ^ a b c Tromans, 135

- ^ Tromans. 136

- ^ Tromans, 14 (quoted), 162–165

- ^ Nochlin, 289, disputing Rosenthal exclamation, and insisting that "in that location must exist some effort to analyze whose reality we are talking about".

- ^ Tromans, 16–17 and run across alphabetize

- ^ Tromans, 135–136

- ^ Tromans, 43

- ^ Tromans, quote 135; 134 on his wife; generally: 22–32, 80–85, 130–135, and run across index

- ^ Tromans, 102–125, covers landscape

- ^ Schimmelpenninck van der Oye, David (2009-12-01). "Vasilij V. Vereshchagin's Canvases of Central Asian Conquest". Cahiers d'Asie centrale (17/18): 179–209. ISSN 1270-9247.

- ^ Brower (1994). Imperial Russia and Its Orient--the Renown of Nikolai Przhevalsky.

- ^ a b c Figes, Orlando, ''Natasha's Trip the light fantastic: A Cultural History of Russia'' (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2002), 391.

- ^ Jenkins, Jennifer (2004). "German Orientalism: Introduction". Comparative Studies of Southern asia, Africa and the Middle East. 24 (2): 97–100. doi:10.1215/1089201X-24-2-97. ISSN 1548-226X.

- ^ Marchand, Suzanne L. (2009). German language orientalism in the age of empire : organized religion, race, and scholarship. Washington, D.C.: German language Historical Institute. ISBN978-0-521-51849-9. OCLC 283802855.

- ^ Irwin, Robert (2001-06-21). "An Countless Progression of Whirlwinds". London Review of Books. Vol. 23, no. 12. ISSN 0260-9592. Retrieved 2021-09-04 .

- ^ Malečková, Jitka (2020-09-24). The Return of the "Terrible Turk". Brill. pp. 26–69. doi:ten.1163/9789004440791_003. ISBN978-90-04-44079-1. S2CID 238091901.

- ^ Tromans, vii, 21

- ^ Beard and Gloag 2005, 128

- ^ Lennon, Joseph. 2004. Irish Orientalism. New York: Syracuse University Press.

- ^ a b Beard and Gloag 2005, 129

- ^ Taruskin (1997): p. 153

- ^ Taruskin (1997): p. 158

- ^ Taruskin (1997): p. 156

- ^ a b Taruskin (1997): p. 165

- ^ "Romantic Orientalism: Overview". The Norton Album of English Literature . Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ a b c Sharp, Joanne. Geographies of Postcolonialism. p. 25.

- ^ Sharp, Joanne. Geographies of Postcolonialism. p. 24.

- ^ Iacobelli, Pedro (2011). "Orientalism, Mass Civilization and the US Assistants in Okinawa". ANU Japanese Studies Online (4): 19–35. hdl:1885/22180. pp. 25-26.

- ^ "At What Betoken Does Appreciation Become Cribbing?". Trip the light fantastic Mag. 2019-08-19. Retrieved 2020-12-18 .

- ^ a b c "Le Corsaire". ABT. Ballet Theatre Foundation, Inc. Archived from the original on 2003-05-06. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ^ a b c d due east f grand h i j thousand l thousand Au, Susan (1988). Ballet and Modernistic Trip the light fantastic toe . Thames & Hudson, Ltd. ISBN9780500202197.

- ^ Jowitt, Deborah. Time and the Dancing Image. p. 55.

- ^ a b c d e McMahan 2008.

- ^ Renard 2010, p. 176.

- ^ Renard 2010, p. 177.

- ^ Renard 2010, p. 177-178.

- ^ Renard 2010, p. 178.

- ^ Renard 2010, p. 183-184.

- ^ Schmidt, Leigh Eric. Restless Souls: The Making of American Spirituality. San Francisco: Harper, 2005. ISBN 0-06-054566-6.

- ^ Renard 2010, p. 185-188.

- ^ a b Sinari 2000.

- ^ Lavoie 2012.

- ^ a b Gilchrist 1996, p. 32.

- ^ Johnson 1994, p. 107.

- ^ McMahan 2008, p. 98.

- ^ Gombrich 1996, p. 185-188.

- ^ Fields 1992, p. 83-118.

- ^ Renard 2010, p. 189-193.

- ^ a b Michaelson 2009, p. 79-81.

- ^ Rambachan 1994.

- ^ Rambachan 1994, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d due east f chiliad Kerboua, Salim (2016). "From Orientalism to Neo-Orientalism: Early and Contemporary Constructions of Islam and the Muslim World". Intellectual Discourse. 24: 7–34 – via ProQuest.

- ^ a b c d e f m h i Mutman, Mahmut (1992–1993). "Under the Sign of Orientalism: The West vs. Islam". Academy of Minnesota Printing. no. 23: 165–197 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Skórczewski, Dariusz (2020). Smoothen Literature and National Identity: A Postcolonial Perspective. Rochester: Academy of Rochester Press - Boydell & Brewer. ISBN9781580469784.

- ^ editor., Lau, Lisa, editor. Mendes, Ana Cristina (eleven September 2014). Re-orientalism and South Asian identity politics : the oriental other inside. ISBN9781138844162. OCLC 886477672.

- ^ Lau, Lisa; Mendes, Ana Cristina (2016-03-09). "Mail service-ix/eleven Re-Orientalism: Confrontation and conciliation in Mohsin Hamid'south and Mira Nair's The Reluctant Fundamentalist" (PDF). The Periodical of Commonwealth Literature. 53 (ane): 78–91. doi:10.1177/0021989416631791. ISSN 0021-9894. S2CID 148197670.

- ^ Mendes, Ana Cristina; Lau, Lisa (Dec 2014). "Bharat through re-Orientalist Lenses" (PDF). Interventions. 17 (v): 706–727. doi:10.1080/1369801x.2014.984619. ISSN 1369-801X. S2CID 142579177.

- ^ Lary, Diana (2006). "Edward Said: Orientalism and Occidentalism" (PDF). Journal of the Canadian Historical Association. 17 (2): 3–15. doi:x.7202/016587ar.

- ^ a b Sharp, Joanne (2008). Geographies of Postcolonialism. London: Sage. p. 25. ISBN978-1-4129-0778-1.

- ^ Mountz, Alison (2009). "The other". In Gallaher, Carolyn; Dahlman, Carl; Gilmartin, Mary; Mountz, Alison; Shirlow, Peter (eds.). Key Concepts in Political Geography. SAGE. pp. 328–338. doi:x.4135/9781446279496.n35. ISBN9781412946728.

- ^ Richardson, Chris (2014). "Orientalism at Home: The Case of 'Canada'southward Toughest Neighbourhood'". British Journal of Canadian Studies. 27: 75–95. doi:10.3828/bjcs.2014.5. S2CID 143588760.

Sources [edit]

- Bristles, David and Kenneth Gloag. 2005. Musicology: The Primal Concepts. New York: Routledge.

- Cristofi, Renato Brancaglione. Architectural Orientalism in São Paulo - 1895 - 1937. 2016. São Paulo: University of São Paulo online, accessed July 11, 2018

- Fields, Rick (1992), How The Swans Came To The Lake. A Narrative History of Buddhism in America, Shambhala

- Harding, James, Artistes Pompiers: French Academic Fine art in the 19th Century, 1979, Academy Editions, ISBN 0-85670-451-2

- C F Ives, "The Great Wave: The Influence of Japanese Woodcuts on French Prints", 1974, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN 0-87099-098-5

- Gabriel, Karen & P.Grand. Vijayan (2012): Orientalism, terrorism and Bombay cinema, Journal of Postcolonial Writing, 48:3, 299–310

- Gilchrist, Ruby-red (1996), Theosophy. The Wisdom of the Ages, HarperSanFrancisco

- Gombrich, Richard (1996), Theravada Buddhism. A Social History From Ancient Benares to Mod Colombo, Routledge

- Holloway, Steven W., ed. (2006). Orientalism, Assyriology and the Bible. Hebrew Bible Monographs, 10. Sheffield Phoenix Printing, 2006. ISBN 978-one-905048-37-three

- Johnson, K. Paul (1994), The masters revealed: Madam Blavatsky and the myth of the Smashing White Club , SUNY Press, ISBN978-0-7914-2063-8

- King, Donald and Sylvester, David eds. The Eastern Carpeting in the Western World, From the 15th to the 17th century, Arts Council of Great United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland, London, 1983, ISBN 0-7287-0362-9

- Lavoie, Jeffrey D. (2012), The Theosophical Club: The History of a Spiritualist Move, Universal-Publishers

- Mack, Rosamond Due east. Boutique to Piazza: Islamic Trade and Italian Fine art, 1300–1600, University of California Press, 2001 ISBN 0-520-22131-ane

- McMahan, David L. (2008), The Making of Buddhist Modernism, Oxford Academy Press, ISBN9780195183276

- Meagher, Jennifer. Orientalism in Nineteenth-Century Art. In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. online, accessed Apr xi, 2011

- Michaelson, Jay (2009), Everything Is God: The Radical Path of Nondual Judaism, Shambhala

- Nochlin, Linda, The Imaginary Orient, 1983, page numbers from reprint in The nineteenth-century visual culture reader,google books, a reaction to Rosenthal'south exhibition and book.

- Rambachan, Anatanand (1994), The Limits of Scripture: Vivekananda's Reinterpretation of the Vedas, Academy of Hawaii Printing

- Renard, Philip (2010), Not-Dualisme. De directe bevrijdingsweg, Cothen: Uitgeverij Juwelenschip

- Said, Edward Westward. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books, 1978 ISBN 0-394-74067-X).

- Sinari, Ramakant (2000), Advaita and Contemporary Indian Philosophy. In: Chattopadhyana (gen.ed.), "History of Science, Philosophy and Culture in Indian Civilization. Volume 2 Office ii: Advaita Vedanta", Delhi: Middle for Studies in Civilizations

- Taruskin, Richard. Defining Russian federation Musically. Princeton University Printing, 1997 ISBN 0-691-01156-7.

- Tromans, Nicholas, and others, The Lure of the Due east, British Orientalist Painting, 2008, Tate Publishing, ISBN 978-1-85437-733-3

Further reading [edit]

Art [edit]

- Alazard, Jean. L'Orient et la peinture française.

- Behdad, Ali. 2013. Photography'south Orientalism: New Essays on Colonial Representation. Getty Publications. 224 pages.

- Benjamin, Roger. 2003. Orientalist Aesthetics, Art, Colonialism and French North Africa: 1880–1930. University of California Press.

- Peltre, Christine. 1998. Orientalism in Art. New York: Abbeville Publishing Group. ISBN 0-7892-0459-2.

- Rosenthal, Donald A. 1982. Orientalism: The Well-nigh Due east in French Painting, 1800–1880. Rochester, NY: Memorial Fine art Gallery, University of Rochester.

- Stevens, Mary Anne, ed. 1984. The Orientalists: Delacroix to Matisse: European Painters in North Africa and the Well-nigh East (exhibition catalogue). London: Purple Academy of Arts.

Literature [edit]

- Balagangadhara, S. N. 2012. Reconceptualizing India studies. New Delhi: Oxford Academy Press.

- Bessis, Sophie (2003). Western Supremacy: The Triumph of an Idea?. Zed Books. ISBN 9781842772195 ISBN 1842772198

- Bitar, Amer (2020). Bedouin Visual Leadership in the Middle E: The Power of Aesthetics and Practical Implications. Springer Nature. ISBN9783030573973.

- Clarke, J. J. 1997. "Oriental Enlightenment." London: Routledge.

- Chatterjee, Indrani. 1999. "Gender, Slavery and Law in Colonial India." Oxford Academy Press.

- Frank, Andre Gunder. 1998. "ReOrient: Global Economic system in the Asian Age." University of California Press.

- Halliday, Fred. 1993. "'Orientalism' and its critics." British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies xx(ii):145–63. doi:10.1080/13530199308705577.

- Inden, Ronald. 2000. "Imagining India." Indiana University Printing.

- Irwin, Robert. 2006. For lust of knowing: The Orientalists and their enemies. London: Penguin/Allen Lane. ISBN 0-7139-9415-0.

- Isin, Engin, ed. 2015. Citizenship Subsequently Orientalism: Transforming Political Theory. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kabbani, Rana. 1994. Imperial Fictions: Europe'south Myths of Orient. London: Pandora Press. ISBN 0-04-440911-7.

- Van der Pijl, Kees (2014). The Discipline of Western Supremacy: Modes of Strange Relations and Political Economy, Volume Iii, Pluto Printing, ISBN 9780745323183

- King, Richard. 1999. "Orientalism and Organized religion." Routledge.

- Kontje, Todd. 2004. German Orientalisms. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Printing. ISBN 0-472-11392-v.

- Lach, Donald, and Edwin Van Kley. 1993. "Asia in the Making of Europe. Book 3." University of Chicago Press.

- Lindqvist, Sven (1996). Exterminate all the brutes. New Press, New York. ISBN 9781565843592

- Piffling, Douglas. 2002. American Orientalism: The Usa and the Eye East Since 1945. (second ed.) ISBN i-86064-889-4.

- Lowe, Lisa. 1992. Critical Terrains: French and British Orientalisms. Ithaca: Cornell University Printing. ISBN 978-0-8014-8195-six.

- Macfie, Alexander Lyon. 2002. Orientalism. White Plains, NY: Longman. ISBN 0-582-42386-iv.

- MacKenzie, John. 1995. Orientalism: History, theory and the arts. Manchester: Manchester Academy Press. ISBN 0-7190-4578-9.

- McEvilley, Thomas. 2002. "The Shape of Ancient Thought: Comparative Studies in Greek and Indian Philosophies." New York: Allworth Press.

- Murti, Kamakshi P. 2001. India: The Seductive and Seduced "Other" of German Orientalism. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-30857-8.

- Oueijan, Naji. 1996. The Progress of an Image: The E in English Literature. New York: Peter Lang Publishers.

- Skórczewski, Dariusz. 2020. Polish Literature and National Identity: A Postcolonial Perspective. Rochester: University of Rochester Printing. ISBN 9781580469784.

- Steiner, Evgeny, ed. 2012. Orientalism/Occidentalism: Languages of Cultures vs. Languages of Description. Moscow: Sovpadenie. [English & Russian]. ISBN 978-five-903060-75-vii.

External links [edit]

| | Wait up orientalism in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- The Orientalist Painters

- Arab earth in art

- Arab women in art

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orientalism

ارسال یک نظر for "Who First Pened the Words Neer a Grecian Art Did Trace a Finer Form More Lovely Face"